- Home

- Helen Limon

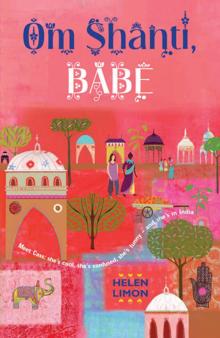

Om Shanti, Babe

Om Shanti, Babe Read online

CONTENTS

The Green Goddess

Cinnamon Toast with a Slide-glide

Death-stare Deluxe

Kiss-kiss-cry-cry

Boys’ Own Fascinating Facts

Karma Cookies

Call-Me-V

Stupid O’clock and the One Musketeer

Princess Priyanka

Oh, Still My Beating Heart!

Dramarama

Tea and Yams?

Mangroves and Lily Pads

Super-serious

Karma-cola

Timepass Things

Gilded Bears

Bath-time for Baby

Plan Bee

Auntie Doré

Om Shanti, Babe

The End (not)

About the Author

Dedication and Copyright

I woke up with sweaty pits and hamster-cage mouth. Five thousand miles on a plane and three dinners in one day but, as a look in my wash-bag showed, no toothbrush!

Running my tongue over furry teeth, I found a trail of crusty drool in the corner of my mouth. I groaned and rubbed my eyes, remembering, waaaay too late, the triple-thick mascara I’d applied back home. Uber-cool Cass arrives in style. Did this happen to people in first class, I wondered? Maybe they had special cabin crew to tidy them up while they slept. Or maybe rich people just didn’t drool.

I unpeeled a curl of hair from my sticky cheek and tried to see through the curtain dividing us from the free champagne and goody bags. I’d begged Lula to go for the upgrade, but she’d gone blah blah blah about it being bad enough needing two tickets.

A TV screen embedded in the seat-back showed a red arrow tracing a path from London and nudging land at our final destination. The cabin crew were starting to pack up the duty-frees and I was running out of time to get to the toilet. I wasn’t sure I could even make it past my snoring neighbour, whose body spilled over the seat like a vanilla muffin.

A pointy elbow war had broken out at take-off, with our arm rest as the front line. Around Dubai I had called – apparently very convincingly – for a sick bag, and he’d moved pretty fast for a big bloke.

During all the fuss, Lula had woken up and shot me a Level Three death-stare. Her range ran from one to seven, starting with thin-lips-furrowed-brow and ending at total-face-freeze. She was asleep now. I watched her lips move and wondered what she was dreaming about.

She turned her head towards me and yawned. ‘Nearly there, Cass. Are you excited?’

‘Just a bit!’

‘You know Bollywood isn’t proper India, don’t you?’

‘Yeah... I bet it’s pretty close though!’

I’d been practising dance routines over Christmas until Lula threatened to cancel our film club membership. How she expected me to learn anything about India was a mystery.

Lula sighed, then peered at me over her glasses. ‘Are your eyes meant to look like that?’

‘Like what?’

She passed me a packet of tissues from the pocket in the back of her seat. I squeezed passed Mr Snoozy and joined the toilet queue.

After I’d rinsed out my mouth, I sat for a while staring into the dull glow of the mirror. My mum was right, my face was a car crash. I’d tried to get the Bollywood Diva look, but my stubby eyelashes and frizzy hair just wouldn’t play. I scrubbed off the mascara and splashed lots of cold water about.

I looked in the mirror again – even more tragic. It wasn’t fair. I knew from the movies that all the girls in India would be really pretty, with long dark hair and huge eyes. How was I ever going to fit in? The seatbelt signs flashed and a grumpy air hostess harassed me back to my seat.

As we came in to land, Lula patted my shoulder and pointed out of the window. Below us were fishing boats painted in bright colours, their nets stretched out across the water behind them. On the river bank, flat-roofed houses sat neatly bunched together between the fields. An early-morning light was just touching the tips of the palm trees, turning them pink and gold.

Lula used this combination of colours in loads of her fabric designs. She called it Kerala Dawn and usually it sold by the truckload. Lula’s shop was named after me, Cassia. Lula said we started, like the cassia tree, as a tiny idea that just kept growing.

Everything she stocked was from southern India, Kerala to be specific, all free-range and nicey-nicey. My mum was kind of a fair-trade freak, but the shop was super-successful and we even had a few celebrity clients.

Just before Christmas, Cassia was featured in a magazine under the headline, Shops to Change the World, but I don’t think the world noticed and now we were having our biggest-ever January sale. It was weird having the shop so quiet. Lula rearranged the shelves a million times and ranted to Auntie Doré about cheap stuff from sweat-shop factories being unfair competition.

Yes, she’d definitely got a bit crazed without some winter sun, so the spring buying trip was brought forward. And guess what? This time I was tagging along too. School? Well, that was another story.

It took forever to get through Customs, and by the time we’d dragged our battered bags to the exit I was ready to shriek. I was in India to get sunshine and glamorama, and all the stupid forms and waiting for our cases was getting in the way!

The doors opened at last and warm air gushed in like a sauna. A mix of hot earth and incense sticks curled up my nose, and a row of ancient buses parked beside the exit doors added exhaust fumes to the fragrant mix. There were about a zillion people milling about too. Most of them were on their phones and the noise was unbelievable.

Lula snapped on sunglasses and launched herself into the crush. She seemed to have special crowd-negotiating powers, but I kept bumping into people and ‘Sorry!’ became a sort of dreary chant.

I was waiting to cross the road when an old man tripped over my bag and muttered something unfriendly-sounding under his breath. His thin legs poked out from the baggy sort-of-shorts he wore. I tried to think nice thoughts, because he was old, but it was pretty gross. My case had left a scratch and a little blood was trickling slowly over his knee.

I looked around for Lula. She was way ahead of me now and slowly disappearing into the crowd. I shouted another ‘Oops, sorry!’ to the old man and then ran after her, yelling ‘Excuse me!’ at random until I caught up.

Lula was waving at someone and, through the crowd, I spotted an emerald-coloured car I recognised from her photos. It was the Green Goddess, but it looked smaller and more old-fashioned in real life. An Indian man was making his way through the crowd towards us.

‘Cassia, I want to introduce you to my friend, Vikram Chaudhury.’

The man smiled and reached out for my bag. His hand was cool and smelled of sandalwood. ‘Namaste, Namaste. Welcome, Cassia, and welcome back to Kerala, Luella. I trust you had pleasant flight?’

Lula experimented with a bit of banter in Malayalam and he only winced once so I thought she must be doing OK. She went to evening classes, and in the weeks leading up to a buying trip she chattered her way through repeat-after-me tapes while she made dinner.

Mr Chaudhury had been escorting Lula around for about three years now. She said he acted as guide, and finder of misplaced stuff. Even in London, Lula left a trail of purses, glasses and keys behind her.

Mr Chaudhury was leading the way back to the car. Lula walked close beside him, deep in conversation. They looked strange together. He was about the same age as her, plumper and not so tall. He wasn’t wearing proper Indian clothes and his short-sleeved shirt was a brighter pink than even Dad would have dared buy. I hurried to catch up with them and linked my arm through Lula’s.

We stowed our bags in the boot and inched out of the crowded car park, horn blaring. Lula sat in the front, so I had the whole back seat to myse

lf. I stretched out my legs and wriggled my toes. Eau de stink-foot lurked around my sweaty shoes. I wondered if Indian girls got smelly feet. Probably not.

Everything went fast-forward when we joined the highway, and the traffic noise went up a couple of levels too. The road was lined with giant adverts for business schools, new apartments and women loaded down with gold wedding jewellery.

A girl pulled up alongside us on a moped. Her helmet was painted with the Indian flag. It matched her outfit. I watched her steer past the front of the car, then she swerved out to avoid a massive pothole in the road. The Green Goddess braked hard. I slid forward in my seat and so did Lula. Her eyes were shut tight behind the giant sunglasses.

Mr Chaudhury patted her hand. It was his bad driving that threw us around so I was surprised when Lula didn’t say anything. She didn’t even push his hand away.

‘Relax, ladies. You will be pleased to note that January is road-safety month in Kerala.’ I could hardly hear him through the blaring of horns and squealing of brakes.

Lula pointed to a sign by the road that urged us to ‘AVOID RASH DRIVING’. Not a chance! Looking around, the only way to do that would be to stay in the airport. Moped-girl sped off and we rejoined the random madness of Ernakulam in rush-hour.

The traffic got worse as we got closer to town but Mr Chaudhury never shouted or got stressed-out. Maybe the little stone elephant sitting on the dashboard kept him calm. Or perhaps it was the St Christopher stuck on to the steering wheel. Lula had one just like it, tied to her bicycle basket.

Lula got a bottle of water out of her bag and passed it over to me. ‘It’s snowing back home, Cass. I bet your school-friends wish they were here with you!’

‘Yeah, I bet they do,’ I replied. But I didn’t really mean it.

‘Year Ten is hard work. I hope they’ll take class notes for you.’

‘Yeah, me too,’ I replied. But I didn’t mean that either.

‘Maybe you could find some nice postcards to send them?’

I opened the window a bit wider and fiddled with the seat-belt. The buckle was hot to the touch and the webbing rubbed against my neck. I took my iPod out of my bag. The battery was flat.

‘Are you feeling OK, Cass?’ Lula was using her Idiot’s Guide to Teens voice.

I ran my tongue over my disgusting teeth. ‘Have you got any mints?’

Lula rummaged around in her bag. ‘No, sorry. Drink some more water.’

‘It’s not cold enough,’ I said, dropping the bottle on the floor.

When I saw Mr Chaudhury frowning in the rear-view mirror I looked away. Why was he looking at me like that? It was kind of rude for him to keep staring at Lula, too. Why didn’t he just concentrate on driving? That was his job, after all.

The heat got fiercer, and my jeans were clinging like the skin on hot milk by the time the car stopped outside our guest house. I slid my feet back into squelchy shoes and looked through a pair of metal gates at the house. The building was three storeys high and white like toothpaste. Swirly trellising around the balconies reminded me of paper doilies at an old ladies’ tea room.

Mr Chaudhury lifted our bags out of the boot and pushed open the gates. A smiley lady in a dark-green saree came hurrying out of the house and hugged Lula. I guessed she must be Mr Chaudhury’s wife.

‘Namaste! Namaste! Luella, my dear, it is so so good to see you again.’ She turned to me and clapped her hands. ‘This must be little Cassia about whom we have heard so very, very much!’ She shooed Mr Chaudhury back to the car, then stood back and studied me. She was so keen to see my sweaty face and terminally frizzy hair that she put her glasses on. I felt like an ornament on Lula’s super-discount shelf. ‘Actually, not so little, I see. She is like you, Luella, but with much of her father too, I think.’

I looked at my sandals. Dust had settled into the spaces between my toes, outlining them in dark brown like a little kid’s drawing. I wondered what Lula had told her about Dad. Probably nothing very good, but that wasn’t fair – it wasn’t his fault he was different.

For ages I had dreams that he’d come back and live with us again. I hoped that he’d change his mind and realise we loved him more than anyone else ever could. Sometimes, when he had a newspaper deadline to meet, he used to yell about the noise I made, and for the first few weeks I thought him going was my fault.

The day he left, I put my cd player in the cupboard under the stairs. Lula found it one day and told me the reason Dad had gone. Then she turned the music up loud, and we cried and ate a tub of ice-cream together.

‘Don’t be shy. All good dishes need a mixture of ingredients,’ Mrs Chaudhury said, flipping her saree shawl over her shoulder. ‘Please come, Cassia, I will show you where you are sleeping.’ She slipped off her shoes and opened the front door.

I picked up my bag and followed her inside. The house was cool and the smell of jasmine and sandalwood drifted along the hallway.

Mrs Chaudhury’s bare feet made a soft slapping sound as she walked. Her toenails were painted dark red. Maybe I should have taken off my shoes too?

I pictured my swollen feet leaving a line of sweaty prints on the polished wooden floor and clenched my toes. I wondered how she would feel about her husband flirting with Lula. Maybe they didn’t mind that sort of thing in India.

Lula and I were sharing a room up on the top floor, with doors that opened on to a flat roof. Tubs of tomatoes lined the edge. I stepped through the fly-screen doors and looked out across the garden. Paper lanterns hung from the branches of a tree, like origami fruit, and from the lawn below I heard the hiss of a water sprinkler.

On the ground-floor terrace I could see Mrs Chaudhury carrying glasses and a tall jug. Mr Chaudhury and Lula had their heads together over the shop order book: the order book I was supposed to be looking after. Lula was even letting him make notes on the pages.

I went back inside and tugged at the doors. The wooden frame stuck and they closed with a bang. Inside the bedroom a ceiling fan turned, gently moving the warm air around just enough to make it breathable. I slid out of my shoes and put my bag on the bed nearest the door. The mosquito nets were a glamorous touch, but I’d expected our room to be a bit more five-star-and-mini-bar. Dad wouldn’t have rated it at all.

I cranked up the ceiling fan and, as the blades began to turn faster, something moved on the wall. A pale-pink lizard had scuttled along and stopped just inches away from the light switch. It blinked. A tiny tongue shot out of its mouth and slid back between its jaws. I stood very still, holding my breath.

The lizard blinked again as I moved slowly away from the wall and ran for the door. Lula would have a fit when I told her and, while Mr Chaudhury got rid of it, I would be able to reclaim the order book. But when I got downstairs no one seemed bothered about mini-beasts stalking the walls.

‘They are called geckos, Cassia. We think of them as our guests. They will help keep your room free of spiders and flies,’ Mr Chaudhury said. His teeth were very white and when he smiled, his mouth crinkled at the corners. What a creep. He’d made it sound like geckos were his best friends and that I was some kind of teen psycho-killer.

Lula looked a bit embarrassed. She had told me loads about India but, clearly, there were some things she’d left out.

When I got back to our room the lizard was in exactly the same place on the wall. As I watched, a fly crawled slowly past it. ‘Well, go on then, get busy!’ I muttered as I undressed.

I washed my hair and stayed under the cool water until my feet wrinkled. Then I brushed my teeth, slid into holiday shorts and was ready to hit the streets.

Lula and the Chaudhurys were eating by the time I got back downstairs. The food smelled of lime and coconut. I wanted us to make a quick exit, but Lula called out from the terrace, ‘Come and have some food, Cassie. Vikram is a great cook – it’s utterly delicious!’

‘I’m not really hungry yet,’ I lied.

‘Are you going exploring already?’

‘Yeah,

I need some exercise.’

I thought Lula would come with me, but it was Mr Chaudhury who stood up. ‘Perhaps I should escort you, Cassia?’

‘That’s kind of you, Vikram,’ said Lula, as she piled more food on to her plate.

‘It’s OK, I like being by myself. Anyway, I’ve already got a guidebook.’

Lula frowned. ‘Well, if you’re sure. Stick to the main road and don’t be long! You could get a couple of tubes of mosquito repellent while you’re out.’ She took a bundle of rupees out of her bag. ‘Perhaps a long skirt would be better for sightseeing, Cass?’

‘Sorry! No time to change now.’ I pocketed the money and headed quickly for the gate.

As it clanged shut behind me, Mrs Chaudhury said something to Lula. I stopped to listen some more, but their voices were muffled by the hedge. This wasn’t exactly how I had pictured our first shopping trip. The pavement outside the gate was all broken up and I kicked a stone hard into the scrubby grass.

The road from the guest house followed the boundary of a dusty playing-field. Tall trees lined the edges and a yellow dog lay panting in the shadows. In the centre, a game of cricket was starting. I stood and watched for a while. The dog wandered towards me. I went to stroke its head, but saw its back was covered in stinky red scabs and changed my mind. Grosserama! Why hadn’t someone called the RSPCA?

I followed the map in the guidebook to the main shopping area and wandered up and down the high street for a while, buying postcards and browsing the gift shops. Most of them had radios going and I practised a few dance moves while I shopped. A couple of local people watched me. I added a bit of swagger to my running-man and finished with slide-glide. They probably hadn’t seen proper street dance before.

I hadn’t walked far, but my belly was making whale noises. The guidebook said there was a popular café just round the corner and, following the map, I shimmied down the next side street.

The breakfast menu was written out on a chalk board by the door, in English, thank goodness. Fruit and cinnamon toast sounded just about perfect and I went inside. I stopped and stared at a painting titled Little Red Riding Hood that hung near the entrance. Miss Hood wore a saree with a bright red cloth draped over her head. A white tiger was lurking in the shadow of a palm grove, but she hadn’t noticed.

Om Shanti, Babe

Om Shanti, Babe