- Home

- Helen Limon

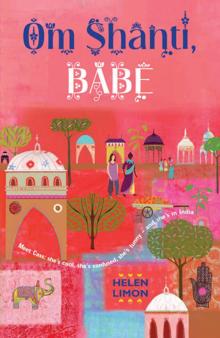

Om Shanti, Babe Page 4

Om Shanti, Babe Read online

Page 4

I remembered Lula putting her wedding ring away in a little box when she and Dad split, and I suddenly felt so sad I could hardly follow what Mrs Chaudhury was saying.

‘This is rava, I believe you call it semolina. Next is sugar, then powdered cardamom, grated coconut, and last of all a little milk. Wash your hands and you can knead this into dough.’

I slid my fingers into the crumbly mixture, cupping my hands into scoops and pressing and folding it around until a soft lump formed. She showed me how to take chunks of the dough and roll it to make little balls. I licked my fingers. The mixture was sweet and smelled delicious. We squished the balls into patties and laid them in a pan on the stove. They sizzled as they hit the hot oil and I watched them bob about in a cushion of bubbles until they turned golden brown.

Whatever happened, Call-me-V would have to be a complete ejit to swap Mrs Chaudhury’s cooking for Lula’s.

‘So, Cassia, while our morning treats are cooling down I shall give you a mehandi, a henna tattoo, and you can tell me all about London. I have never been and I am looking forward to seeing it.’

‘Are you going on holiday?’

‘I am hoping to see the Queen, and Vikram wants to visit your mother’s shop, of course.’

My stomach gave a lurch. I looked up at Mrs Chaudhury. Did she suspect anything? She was so nice. How could Lula do this to her? Why didn’t she find someone in London, someone like Dad? Well, not exactly like Dad – clearly that wasn’t the answer.

Mrs Chaudhury was pointing at some photos from a magazine. The girl’s hands were completely covered with lines and swirls traced out in orange dye. As I looked down at the pictures she gently stroked my fingers. ‘I think this one would be very nice for you, you have such pretty hands. It is a pity you are biting your nails.’

She took a small cone-shaped package off the shelf behind her and snipped the pointed end with scissors. I was embarrassed when she lifted my sweaty hand on to her lap, but the silk felt cool and reassuring.

‘Shall I put somebody’s initials in the design?’

On a weird impulse I asked her to paint JG for Jonny Gold, surrounded by tiny stars, on to the inside of my wrist.

Smiling, she asked if that was my boyfriend’s name and I said, ‘Yeah, right, I wish!’

Mrs Chaudhury gave me a strange look and said, ‘Be careful what you are wishing for, my dear,’ in a deadly serious voice. ‘Tell me, who is this Mister Jolly Gee you are thinking about?’

‘He’s an amazing singer in this band and he writes all the songs. He’s really famous in England.’

‘And why do you like him so very, very much?’

‘Because he’s really cool and he cares about stuff and when I listen to his music it’s like he almost knows who I am. I mean, if I met him, I’m completely positive we’d get on really well straightaway.’

‘He sounds like a dream, my dear, and sometimes that is how things should stay.’

‘Mrs Chaudhury, have you and Mr Chaudhury got any children?’

‘Me and Vikram with children?...No!’ She looked astonished and then started to laugh. A fat drop of henna flew out of the packet and landed on my arm.

‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to be rude.’

‘Cassia, I have a grown-up daughter, but Vikram is not my husband, he is my brother-in-law!’

‘Your brother-in-law?’ I stared at her. My mouth was hanging open and there was a low whining sound in my head like a million bees were nesting between my ears.

‘Yes, my husband, Vikram’s brother, was killed in an accident when my daughter was a little girl and so we came to live here, with Vikram.’

‘Oh, that’s nice... I mean, I’m really sorry about your husband.’

‘Yes, Cassia, I am sorry too. Being a widow lady is not very nice, but Vikram is a kind, kind man. Now hold still and let your Auntie Lalitha finish this mehandi. From the look on your face I think we are both needing some milk and cookies!’

The next day, a tuk-tuk was parked ready for our trip to the spice market. So after cinnamon toast and mango juice at the guest house, Lula and I made our way through the human and animal traffic towards the trading district, Mattancherry.

We seemed to have escaped from Call-me-V, but instead of giving me all her attention in a good way, Lula was acting annoyed. She asked me why on earth I’d thought Vikram and Lalitha were married, which I said was a pretty dumb question, as they were the same age, lived in the same house and were both called Chaudhury.

We passed through a really old bit of Kochi in silence. Falling-down houses with trees growing out of the roofs lined the road. Looking through the padlocked, iron gates at the grand entrances I thought some seriously rich people must have lived here once and I wondered what had happened to them. Why did they leave their houses to just fall down? If they didn’t want them, then why didn’t they let other people live in them?

I leaned out of the tuk-tuk as we passed a palace. The driver said the Portuguese built it five hundred years ago as a present for the king. It didn’t look much older than the other buildings, but tourists and a party of local school kids were queuing on the stairs waiting for the doors to open.

I wanted to know more about Call-me-V, but I couldn’t find the right words to ask my grown-up mum if this was a serious boyfriend thing or just a... what?

Serious relationships were all that adults did, wasn’t it? And how did her being someone’s girlfriend and my mum work when we were all together? What if I wanted ice-cream again? Would she let me or would it be Call-me-V’s rules while we were here? What if he was really mean to me? Would Lula take my side or buddy up with him? And what if stuff happened that was more serious than ice-cream? Would she still love me?

We parked on Bazaar Road and started our buying expedition with perfumes. This was where Lula got the incense sticks and fragrance oils we sold in the shop. A red-and-black painted board outside the door listed all the different flowers they used in their mixtures. Tiny glass bottles lined the mirrored shelves of the shop.

The owner, Mrs Jaffrey, knew we were coming and she’d prepared a selection of new mixtures for Lula to try. The not-talking thing between me and Lula was making me feel sad and it was a relief not to be alone any more. We went in and slipped off our shoes.

Perched on a stool by the counter, drinking juice, I watched as Mrs Jaffrey laid out the sample bottles. Then she put small drops on to our skin and explained that each one was good for different things. Some were just perfumes, but others, like the massage oils, could help you feel better too. With some oils, like Rose, just the smell was enough to change your mood. I wondered if there was a mixture for difficult mothers.

Lula said she was looking for a bestseller and we sniffed and sighed our way through Green Orchid, Kerala Flower and something with juniper that Mrs Jaffrey said was very good for cellulite – I could see from Lula’s expression that a couple of pints would be in the post before we left.

I tried to take charge of the order book, but Lula took it off me and wrote down the orders as she went along. This was supposed to be my job and I was left sitting on the stool with no one talking to me and with nothing to do.

I was bored and fed up, but Lula loved trying to haggle over the prices. She started off with an insanely low offer, but Mrs Jaffrey wasn’t playing. There was a bit of, ‘I am just a poor shopkeeper’ on both sides, but Mrs Jaffrey didn’t cave. Lula tried hard, but I think the perfumes ended up way more expensive than she’d budgeted for.

Once we’d finished writing up the orders and arranging shipping, Mrs Jaffrey said she had a surprise and reached under the counter. She presented me with a tiny blue bottle with a silver lid and a purple tassel.

‘Cassia, this is a very special perfume, I hope you will like it. It is a blend of Lotus for your smile, cinnamon for your name and even a bit of pepper for your energy.’ She opened the bottle and passed it over to me.

I took a deep sniff and a sweet flowery smell curled up my nose. It m

ade me think of Sunday mornings, when Lula lights incense sticks and we re-stock the shelves together. I suddenly felt homesick and I wanted to get out of the shop and be in the sun.

Our next stop was the ginger factory. It was built around a huge courtyard and the knobbly roots were laid out on the warm stone floor like a giant carpet. Lula said they would stay there, drying in the sun. They didn’t have long to bake. The monsoon was due in another few months, and then this whole place would get a daily bath.

Lula bought a few samples for a catering business she’d started with some friends. At Christmas, Auntie Doré had said Lula should ‘focus on the shop for pity’s sake, Loopy Lu!’

‘Well, I think it is time for lunch and a nice cup of tea,’ Lula said, sounding more cheerful. I hoped she had got over her bad mood and was going to be nice to me for a while.

We found the tuk-tuk and made our way to the Spice Café. As we went inside I saw Call-me-V sitting at a table by the waterside. Of course, that was why she had cheered up. It was him she was happy to see, not me. Call-Me-V checked Lula’s list in the order book. I tried to look over his shoulder.

‘Have you talked to any of your friends at school yet, Cass?’ Lula said it in a super-casual voice, but I didn’t bite. I definitely didn’t want to talk about that stuff in front of Call-Me-V.

‘How’s Auntie Doré getting on in the shop?’ I said.

‘Well, you know Doré, always ready with business advice,’ Lula said in a really sarky voice.

‘Maybe you should listen to her sometimes.’

‘When I want advice like that I’ll ask Cruella De Ville!’

‘Yeah, cos she’s available for a quick chat!’

‘Cass, if Doré had her way, we wouldn’t bother about organic, fair-trade or anything else. She thinks I’m daft to work the way I do and maybe she’s right, but it’s MY shop and I’ll run it MY way or...’

She was blasting out a scary, goddess-level death-stare and had my hand in such a tight grip my fingers were turning blue.

‘OK, I get the point, you can let go now,’ I said.

She glanced down and gave the mehandi a good long look. ‘Vikram has arranged tickets for a theatre show for us all. I told him you were interested in dancing. Isn’t that nice of him, Cassia?’ she said, looking all dolly-daydream at Call-me-V.

Actually a dance show sounded pretty cool, but I didn’t want to go with him. I didn’t even want to go with Lula. Didn’t she realise what a terrible example she was setting? I knew he wasn’t married or anything now, but everyone knew holiday romances were a disaster.

It was just like my Peacock Spring book. There was Una, falling in love with the poet, Ravi, and getting trashed by her stepmother, Alix. I was beginning to see why, for Una, going back to boarding school might look like a solid plan B.

On the way to the theatre Call-me-V explained that the style of the performance they were doing was called Kathakali. It was a mixture between a musical and a play and there weren’t any words, as the actors sort of spoke with their hands and eyes. Call-me-V said they trained all their lives to learn the stories and the parts properly.

It was sounding a bit too old-school for me and I was beginning to wish I’d gone for belly-ache and a trip back to the guest house. But with our tickets, we got a card that explained the extreme facial expressions, which really helped to sort out what the characters were up to.

The performers got ready on stage and while they were doing their make-up Lula got her camera out. Almost everyone in the cast was a God or Goddess, and the stories were all about the battle between heavenly worlds and demon worlds. All the actors were men, but they seemed to be making a real effort, aside from the coconut-shell boobs, which would have made some of Dad’s theatre friends kind of hissy.

Lula put her camera away as people arrived to take their seats. The music started and everyone settled down. The story was introduced by the main singer. It was a demon woman versus heroic prince set-up and everyone who’d read the story knew that in about two hours’ time it would end badly, for her.

Our seats were under the balcony and every few minutes a pistachio shell landed on the floor in front of me. I looked up and scanned the faces staring out at the stage. They were mostly in deep shadow, but a light from the stairs caught the pistachio-eater in silhouette. It looked like one of the little kids from Mr Rao’s restaurant. He was drumming his hands in time to the music and this was sending shells spinning off the balcony railing.

‘Look! It’s your friends up there,’ I said.

Lula looked up and shook her head. ‘I don’t think so.’ Her chair scraped noisily along the floor as she twisted back to the stage, and the boy looked down. He waved at me and put drinking straws into his mouth like a walrus. He looked so funny I couldn’t help laughing. The people seated around us started shushing and Lula hissed, ‘For Goodness’ sake, Cassia, stop fidgeting.’

A shower of empty shells landed on my head and when I looked up again the boy was sitting on his mother’s lap and the adults were all looking a bit annoyed.

At the interval, walrus boy came running up and offered me a handful of sweaty, green pistachios. I took a couple and cracked them open. I guessed his parents hadn’t seen us because there was no sign of them downstairs or up on the balcony, and Lula was pacing about like she wanted to leave.

‘Aren’t you going to say hello to your friends?’ I asked at the end of the show, as she walked straight towards the exit.

‘No, Cass, I don’t think that would be a good idea,’ she said. Her face looked tight and witchy.

Just as we reached the doors, Mr and Mrs Met-at-the-Restaurant appeared. For a second they looked as uncomfortable as Lula, but then all the adults did this freakish face-morph thing and it was full-on ‘How lovely to see you!’ and ‘Wasn’t the show wonderful!’

Watching them, I almost believed everything was OK, until we were in the tuk-tuk going home and I felt Lula’s hand. Her fingers were trembling and as cold as ice lollies.

It felt like the middle of the night when Lula cajoled me out of bed. I blundered about in a daze, trying to get dressed with my eyes closed. They cracked open once I reached the bathroom, but after a look at my scarecrow hair I shut them again.

Lula had decided on the public-transport option and we were booked on the early-morning commuter train that would take us up the coast, north to Kannur. It seemed Call-me-V was driving us as far as the station. But after that I was looking forward to it being just me and Lula again, for a while. As he loaded our bags, he showed me the triple-decker tiffin tins (India’s completely brilliant version of the picnic hamper) stowed in the boot.

‘My sister-in-law is worried you are not getting enough to eat, Cassia. She thinks you are having hollow legs and is blaming your mother for naming you after a tree!’ he said.

We crossed the bridges back to the mainland and parked outside the railway station. The platform was like a zombie film, with sleepy people staggering on and off the train. Studenty tourists swung their enormous backpacks around like weapons of mass decapitation. Inside the carriage the aisles were packed with boys selling drinks, newspapers and snacks.

Call-me-V pushed on ahead and we Excuse-me’d our way to our seats. He seemed to be hanging around a bit, getting our cases up on the rack and ordering drinks. When the whistle blew I expected to see him make a run for the doors. But he settled himself down next to Lula and opened out a newspaper.

Once the train set off, Lula inflated a travel pillow and rested her head against the window. She looked really exhausted. A deep frown made a ridge between her eyes and she was twisting an earring as if it could grant her three wishes.

Perfect, just perfect. I thought I’d have Lula to myself for a bit. I really wanted to talk to her about school and stuff, but I couldn’t while Call-me-V was poking his nose into our lives.

In London, Lula had kept saying things like ‘When you get back to school, Cass’, but I never wanted to go back. I couldn’t

go back.

I’d wanted to tell her about what was happening to me with Rachel and the other girls in the dance group loads of times. But lately, Lula had been so stressy and unpredictable, I was scared she’d throw a major emo fit and go stomping off to the headteacher, and then she’d find out I’d been skipping lessons and it would get even worse. All those times she thought I was at dance practice when really I was hiding out in the library.

I’d really hoped that here, in India, Lula would relax and things would go back to how they used to be, when I could tell her anything and she’d make it all right. She used to be Mrs Fixit, but recently she’d changed. I knew she couldn’t just magic my problems away, but I did expect her at least to have time to listen. Now Call-me-V was always around and ruining everything.

I stared out of the window. The view of palm trees and fields reminded me of the plane journey coming over. It felt like a million years ago, and pretty much everything was different from what I’d expected. So much for escaping from my problems – it felt like I’d just got a whole new set to worry about.

I opened my book. Una was in trouble, too. The governess, Alix, had gone a bit psycho because she had stolen whisky and Una thought she should tell the truth and not let a servant get sacked for it.

I felt a bit sorry for Alix (even though she was a horrible person) because her mum was Indian but her dad wasn’t, and she didn’t fit in with the English people or the Indians, and it made her scared and a bit mad. If Edward wasn’t such an old-school dad it would probably have been OK. But he was too busy working to see what was happening.

Gradually everyone around me either fell asleep or pulled out laptops and started tippy-tapping away. We’d not been travelling long but my stomach was already rumbling. Lula and Call-me-V were dozing, so I took my tiffin box to the corridor between the carriages.

The train doors were left open and the countryside trundled slowly past in widescreen. I sat with my feet resting on the outside step and watched people start their day. A group of women were washing clothes in a river. Right next to them, others were cleaning cooking pots and bathing. I tried to imagine what it would be like not having your own bathroom. My mouth felt weird when I thought about cleaning my teeth in washing water.

Om Shanti, Babe

Om Shanti, Babe