- Home

- Helen Limon

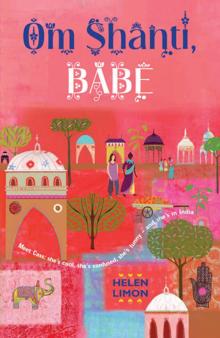

Om Shanti, Babe Page 6

Om Shanti, Babe Read online

Page 6

I scrambled up to the first support and then, gripping the trunk with my legs, I hauled myself along to the second and then the third rung. Apart from getting properly bruised knees, it was pretty easy. A few more hefts and I’d reached the top of the trunk. The penknife Priyanka gave me was wedged in my back pocket, and as I twisted round to get it I looked down.

Priyanka and Lula were watching me from the garden. ‘Can you see any bananas yet, Cass?’ Lula called up.

I tilted my head back and looked into the leaves. There were no bananas. Instead there was a generous bunch of what even I recognised were coconuts.

‘Banana palms are the other side of the house, Cass,’ Lula laughed.

In fact, they both laughed quite a lot. Priyanka’s ‘hilarious prank’ was obviously a family favourite.

I decided to stay in the tree for a bit. My eyes were still stinging from the sea-water, but from up high I could see the ocean and the beach, girls playing netball, and the white birds picking flies off the buffaloes’ backs.

‘Come on down, Cass,’ Lula called. ‘There’s a lime soda ready in the kitchen.’

I didn’t reply.

Once they had gone back inside, I climbed down and took a long shower. I just left my hair to sprout as usual. I looked at the green top Priyanka had laid out for me and I even held it up in front of the mirror. She was right, the colour did look really nice with my eyes, but I couldn’t wear it – I was too upset about the coconut joke. So I put it back in her wardrobe.

I had thought Priyanka would be more ordinary and that she’d like me and I’d feel like the special one. But instead I felt like a stupid, frizzy-haired lump, whose mum laughed at her because she couldn’t even tell a banana tree from a coconut.

As it got dark, the guests started arriving, all loaded up with dishes of steaming rice, fish, coconut-scented curry and boxes of sweets.

Lula had made some chocolate cup-cakes as our contribution. Priyanka saw them and I heard her say, ‘Oh Goodness, Auntie Luella, those do look delicious!’

Lula beamed at her with pleasure.

I watched Priyanka’s face as she carefully picked one out. Maybe she’d been warned about Lula’s cooking because I noticed she only broke off a tiny piece before setting the cup-cake down again.

The food table was getting crowded with people arranging their contributions. Everyone was very glamorously dressed – except for me. I hadn’t packed anything partyish so I was stuck in jeans and T-shirt. Priyanka’s loaned salwar would have been perfect.

As a full moon rose above the trees, a group of musicians appeared and set up their instruments in the middle of the garden. They had brought two kinds of drum and a sitar. The neighbour’s children taught me a routine from their favourite film, so I showed them a few street-dance moves which made them laugh a lot, and after a bit of practising we twirled and stomped our way round the garden.

Dancing cast a spell on me. Christmas, school and mean girls floated away into the moonlight. This would be what my life would be like every day when I was older, and on TV. There’d be dancing and parties and glamour, and Jonny Gold and his band playing just for me.

As soon as everyone had cleared their plates, Saachi asked the musicians to take a break. And once the garden had gone quiet, she started to speak. I could tell by people’s expressions that it was all serious stuff and she had to keep stopping as angry muttering broke out. Priyanka did a whispered translation of the most important bits and I thought I got the picture.

A developer had bought a big piece of land along the beachfront and was building a luxury hotel complex on the cliffs. The mangrove trees, which protected the coast from flooding, would be cut down, the beach would be fenced off and many of the villagers would lose their homes. The developers wouldn’t talk to anyone from the village and no one was sure where their money was coming from.

Saachi had been doing some investigating through her legal contacts and she was trying to find out who was behind the scheme. Anyway, everyone had got their angry heads on and Saachi got a round of applause for her efforts. Lula did a little speech about how much she loved Kerala, Call-me-V beamed a big smile at her, and the adults got all teary-eyed about shared values and blah-de-blah.

I sat by myself and listed to the waves rolling on to the beach. It sounded like Saachi had done loads of research and I wondered why she cared so much. It wasn’t like her mansion house would be going anywhere.

The next morning at breakfast there was no sign of Call-me-V and I guessed he’d left after the party. I wondered if he’d gone back to Kochi or maybe he had a guest house near here, too.

Lula was only picking at her toast and she kept twisting her earrings round and round. Maybe she was missing him already. Poor Lula, I’d never thought she might be lonely before. She’d been by herself since Dad went.

A year before he left, he covered a story about two male penguins in New York zoo who’d become a couple. They even pretended a small rock was an egg and took turns to sit on it. When they turned the story into a book, he got it for me for Christmas. I was little then, and he used to sit on the end of my bed and read it. He did all the voices and everything. I suppose that’s when he realised he wanted to live a different life. I knew he still cared about me and my mum, but we weren’t enough any more.

I hated hearing them fighting and the things they said didn’t make sense until much later. When Lula explained that Dad was leaving us because he had fallen in love with another man, I asked her if he would still love me when I grew up, even though I was a girl. She hugged me until I practically couldn’t breathe.

But Lula would be OK. She was with me and Saachi and Priyanka now, so she wouldn’t miss Call-me-V for long. We were going fabric-buying later, just the two of us, and I decided I would be super-nice and helpful to show her that she didn’t need him around any more.

Priyanka’s grandma, Granny-ji, arrived while we were eating. She poured some tea, ‘the cup that cheers’, and asked me if I was feeling ‘in the pink’. I replied that I wasn’t quite sure.

Saachi explained that she used to be an English teacher and gave lessons to families in the village, using old children’s books. Saachi said that for years she’d believed that Enid Blyton’s Famous Five were real British kids. I wondered if she missed being a teacher now she was old and I promised to send over some top-quality, modern teen-lit. Then Granny-ji patted her chest and said, ‘Oh, still my beating heart!’ which made Lula laugh so much she spilt her coffee.

Saachi told Lula that Priyanka still hadn’t decided on what career path she was going to follow, but that she was seriously considering Law.

‘Amma, you’re so boring! You think everyone should study Law.’ Priyanka pushed her breakfast away, uneaten, which was really rude of her.

‘There’s nothing wrong with being boring, Priya. As a matter of fact, if you work hard, you can make a difference in the world, you know.’

‘Amma! I want a profession with much more stylish outfits.’

I saw Lula smile, but I thought Priyanka was being a spoilt brat.

Saachi didn’t reply, but she looked a bit cross.

Priyanka asked me what I wanted to do and I told her about being a dancer. She said girls here went to dancing school when they were really young, and studied for years if they wanted to do it seriously. Things were different in London, I said. Then I explained about helping Lula in the shop, too. I saw Lula and Saachi exchange a look and no one said anything after that.

We cleared the table and got ready to go out. Saachi offered to give us a lift into town. I thought Priyanka was going to school, but she appeared from her room holding a sketch-pad. Apparently, Princess Priya had taken the day off and Lula seemed really pleased. So it wasn’t going to be just the two of us after all.

I shut the door of our room with a bang. It wasn’t fair. Lula was my mum, not hers. I didn’t see why Lula wanted her to tag along. I could help, but Priyanka didn’t know anything about the shop.

<

br /> As we cleared the hill out of the village, I saw the site of the hotel development. Saachi asked if we wanted to take a closer look and stopped the car at the side of the road. Priyanka stayed in the car with Lula, but I followed Saachi up the path.

The building site looked empty, and we walked beside the wire fence which went all the way around the plot. Golden bricks, like chunks of cinder toffee, were stacked in neat piles against the edges. The complete circuit took us to the edge of the cliff overlooking the sea.

Whoever ended up staying in this hotel was going to get an amazing view, I thought. I wondered how I’d feel if I was a rich person wanting a beach holiday. Would I care about a few mangroves and some village houses? I could definitely picture Auntie Doré here, that was for sure. I walked over to the board with the artist’s impression on it.

‘Wow! Saachi, come and look!’ I called.

She followed me over and stared up at the drawing.

The picture of the tall glass tower had been partly covered in spray paint and the words BEARS BEWARE were graffitti’d over it in gold. Someone had done a very careful job on the letters, even though the words didn’t make much sense.

‘But I do not understand... there are no bears near here,’ Saachi said.

The name of the investment company, Auramy Incorporated, was just visible through the paint.

‘Wouldn’t it be nice to have a hotel with shops and restaurants here, Saachi?’

‘As a matter of fact, I don’t mind them building a hotel. Tourists bring money and jobs. But this is not the right place. The costs to the people and the environment are much too high.’ She looked so fierce when she said it, like the Goddess Kali gone nuclear, I felt a bit sorry for Auramy Incorporated when she caught up with them.

‘When did you decide to be a lawyer, Saachi?’

‘When I was old enough to notice how the rich treat the poor.’

‘Do you think Priyanka will feel the same as you?’

‘Priya notices only frocks at the moment, I’m afraid. And what about you, Cassia, why do you want to be a dancer?’

I started to answer her, telling her stuff about fame, and parties and being on TV, but somehow saying it out loud to Saachi, it didn’t feel real any more. I couldn’t find the right words and my voice didn’t sound like I really meant it.

I stopped talking and felt my face go red. She probably thought I was an idiot. But she wasn’t looking at me with a for-goodness’-sake expression, she was really interested and was taking my answer seriously.

I managed to mumble something about how being part of the dance group, us all working together to put on a show, connected me to something bigger than myself.

Then she smiled and nodded her head. ‘That is how the law feels for me, too. Putting something right in the world, even something quite small, makes me feel that what I do matters and that I matter, too. You know, we have more in common than you might imagine, Cassia.’ She linked arms with me and we walked away from the building site together.

When we got back to the car, I saw Priyanka passing Lula her sketch-book. They had their heads together while Priyanka turned the pages, showing Lula drawings of wedding dresses and pictures cut from fashion magazines.

As I climbed into the back seat, Lula closed the sketch-book. I wanted to tell her about seeing the graffiti, but seeing her snap the book closed made me feel shut out. Like there was a secret between her and Priyanka and I wasn’t included.

The weaving workshop was just how Lula had described it. Piles of fabric parcels labelled with exotic destinations filled the office like giant sugar cubes.

Back at the shop, my Saturday job was to check the delivery and carefully cut through the stitching that held the parcels together. Then we’d go through each bale of fabric and check it against the order book.

The packaging was covered with colourful customs stamps and it seemed a waste to just chuck it away. I’d had the idea of turning it into carrier bags for the shop. I’d cut out big squares, making sure to get a bit of the coloured customs stamps on each panel. Then I stitched them together with waxed thread. Making the bags was how I earned my allowance.

When we moved out of the office and into the busy weaving shed, it became very hot even though all the windows were open and fans whirled in the roof. Lula looked at the colours on the wooden weaving machine while the man operating it tugged on a string, making the thread fly from side to side.

I watched his feet, as he controlled the up and down criss-crossing of the cotton with foot pedals. The fabric appeared really slowly, line by line. I realised that this was where Lula’s ideas turned into real stuff and, watching her face, I could see how much she loved it.

The weaver was sweating and taking big drinks of water as he worked. He said his kids wanted to move to Bangalore and get office jobs where they would get better money and proper holidays. Lula said she’d heard about all the call-centres, ‘summoning the young like the Pied Piper’. Then she laughed and said she expected to be talking to his kids about her overdraft some day soon.

After the first few centimetres of fabric were visible, Lula looked relieved and I guessed the sample was working OK. We all went back into the design room and the manageress got out a book full of fabric squares. This fabric was much finer than the material Lula usually got for cushion covers and bedspreads.

Priyanka kept holding pieces against our skin, then making notes in her sketch-book. She picked out an emerald green square which changed colour to a soft pink when it caught the light, and held it against my face, then she and Lula made a sort of death-by-chocolate-delicious noise together and Priyanka scribbled in the sketch-book again.

They obviously didn’t want me hanging about, and I really needed a cold drink, so I left them to it. There were shops on the road, but after my Odomos humiliation I was a bit nervous about setting off alone.

‘Are you looking for something?’ The manageress was standing beside me.

‘I’d like to get something to drink.’

‘I am arranging to get chai for your mother – would you like one, too?’

‘OK.’

I must have sounded a bit disappointed because she said, ‘The shop sells drinks out of the fridge. Maybe you would prefer cola or a lemonade?’

‘Oh, that would be great!’

She told me how to say ‘Please’ and ‘How much?’ and I set off up the road, practising ‘Dayavuchetu’ and ‘Etra?’ under my breath the whole way.

The boy working in the shop looked a bit like Dev, and when I tried out the words the manageress had taught me he smiled, which made me blush, and then I got so embarrassed about blushing that I started to choke on my drink. My eyes watered and cola was leaking out of my nose.

He stopped smiling and looked really worried. It probably wasn’t good for business to have a customer explode in your shop. Seriously, why was I such a freak? I would never make friends here, or anywhere else.

Maybe Rachel had done some kind of voodoo curse on me from London. After all, I had nearly fallen out of a train, practically drowned, and now I was choking to death. It wouldn’t be so bad if it had all happened in private, but someone was always there, watching me. Though if Dev hadn’t come along I’d be a train-mangled freak, which was worse.

I wondered where Dev was now – a million miles away, probably. Maybe he was busy rescuing another girl-in-peril. That thought made my throat close up again.

My eyes were watering really badly now and the boy handed me a packet of tissues from the counter. I ripped the wrapper open and buried my boiling face in a nest of cotton. I stood very still, gasping and wheezing until my breathing got normal, then I tried another sip of Coke. The bubbles helped and I set the bottle back on the counter, which was stacked high with that day’s Indian newspapers.

Staring up at me from the front page, I saw super-handsome Jonny Gold’s picture. My breathing went funny and I quickly swallowed the last of the drink. I had no idea what the story was abo

ut, but I had just enough rupees left to buy a copy so I put the money on the counter and rushed back to the weaving workshop.

Saachi’s car was pulling up by the entrance when I got back, and Priyanka and Lula stood waiting by the door. They were chatting together and Priyanka had a parcel tucked under her arm. I could see bits of fabric sticking out of it. I wondered if they’d even noticed I’d been gone. I tore out the Jonny Gold article and stuffed it into the pocket of my jeans. I had no idea how I would read the story, but I certainly didn’t want to share Jonny Gold with Priyanka.

Back at the house, I ran to my room and grabbed my swimming costume. Priyanka was in the kitchen when I got downstairs, but her sketch-book was lying on a table in the hallway.

I picked it up and started flicking through the pages. In the beginning it was all traditional English wedding dresses, big meringues of white satin and little kids in pink. Then, as I flicked through, the pictures got more Indian-looking, more colourful, with layers and beautiful patterns printed on to the fabric. I could see Priyanka was really good at drawing - no wonder Lula made a fuss of her.

I felt a stab of jealousy and turned to the middle of the book. Even the faces on the figures looked lifelike – and weirdly familiar. There was a picture of a pale girl in an emerald saree-style dress, and standing next to her was an Indian girl in blue with advert-perfect hair. Underneath, in very neat writing it said, The Bridesmaids.

The book suddenly felt very heavy in my hands. I turned the next page. In the same neat handwriting Priyanka had spelled out Auntie Luella and Uncle Vikram-ji’s Wedding! And underneath the words, in a beautiful pink-and-orange dress, was a picture of Lula, my mum, Auntie Luella, smiling and happy, and standing beside her was the bridegroom, Call-me-V.

The air in the room suddenly popped and then everything fell away. I had walked over a cliff, cartoon-style. Only it wasn’t a cartoon, it was real, and I wasn’t running in mid-air, I was falling fast.

Om Shanti, Babe

Om Shanti, Babe