- Home

- Helen Limon

Om Shanti, Babe Page 8

Om Shanti, Babe Read online

Page 8

‘By the temple pool. It cannot be true!’ she shrieked.

‘What? Where?’

‘Jonny Gold!’

‘Oh purlease!’ I said sarcastically, but as I looked over to where Priya was pointing, I saw she was right.

Even with a baseball cap pulled down over his eyes, it was unmistakably him. He was moving away from us, so I set off at a run. I didn’t know how Priya had spotted him, but this was my chance to meet Jonny Gold and I couldn’t let her slow me down.

‘He’s heading for the taxis. We have to hurry!’ I shouted. She still had hold of my arm and I was practically dragging her towards the road.

The Theyyam was getting busier and I struggled to make my way against the crowd. I quickly gave up on ‘Excuse-mes’ and barged my way through. I had shaken Priya loose and I was moving fast. I could just see Jonny’s hat bobbing above the crowd and despite the crush of bodies, I seemed to be getting closer.

I looked around to check on Priya, who was making a high-pitched yelping sound like a crazy person, but when I turned back Jonny had disappeared into a surge of new arrivals. I jumped up and down, trying desperately to keep his hat in sight. Finally, I escaped out of the crowd just in time to see Jonny getting into a waiting car. I watched his tattooed arm, dangling out of the car window, as it disappeared into the distance.

Priya crashed into me and grabbed my wrist again. ‘NOOOO!’ we both wailed together and I realised we were hugging each other.

Lost in the craziness of actually seeing, then losing, Jonny Gold, neither of us said a word. Slowly, we made our way to where Granny-ji was sitting. We didn’t bother fighting against the crowd any more either, we just let it push and pull us around like two beach balls bobbing on the tide.

‘Was it really, really him?’ Priya said.

She looked so serious I started to laugh. Then she started to laugh, too. We got louder and louder and more and more hysterical. People were beginning to stare. I got a stitch in my side and had to stop.

Granny-ji was awake when we finally reached her chair and she clapped her hands together as though she was really pleased to see us. I noticed Priya and I were walking with our arms linked together, just like friends out having a good time.

And it was true. Not-so-perfect Priya was a secret Jonny Gold grunge girl, and that meant we were bonded in fan-dom for ever.

We got up late the next morning after an OMG-we-love-Jonny-Gold sesh that went on well past midnight. In the middle of the night, I’d remembered the newspaper with his picture on the front page, the one I’d bought during my choking fit in the shop.

I gave it to Priya to translate and she said it was a story about the golden one’s new music video. Apparently he was looking for a paradise beach to use as a background and had decided Kerala was the perfect place to start looking.

‘Can you imagine how amazing it would be if he came here?’ Priya shrieked when she read it out. ‘Amma would have a nervous breakdown. She absolutely hates pop music and all those people tramping over her precious ecosystem. She’ll go mad!’

I felt a bit uncomfortable hearing Priya talk about her mum like she was crazy. Loopy Lu was one thing, but Saachi was something else.

The last few days, Saachi had been really nice to me and told me lots about her research, which was not the yawn-fest I’d imagined. She’d defended exploited workers, stood up for women’s rights and had even been arrested a couple of times. She talked to me about when she realised the law could help to change things and how important it was that people with big voices stood up for people whose voices didn’t always get heard.

She said, ‘Life isn’t all ha ha hee hee, Cassia, but there is real joy in realising that everyone and everything is connected.’

Lula and Saachi met in England when they were students. They were eighteen years old and a long way from home. Lula was studying Design. She told me she’d said hello one morning at the library because Saachi looked so glamorous. It turned out that Saachi was looking for a flatmate and she was happy to share with Lula, even though she couldn’t cook and was really untidy.

On Saturdays, Saachi searched the west end of the city for Keralan spices. Lula went with her and that was where her obsession with Indian fabrics started.

They explored the castles of Northumberland and Hadrian’s Wall. Saachi laughed about the weather-related graffiti the Romans left behind and said she’d felt like adding a bit of her own. Lula made a full-length wool coat with an extra-thick lining for her. Saachi still has it hanging in the cupboard.

They took a market stall at the quayside on Sunday mornings and sold rice pancakes, cushion-covers and hand-made sweets to people strolling along the banks of the river Tyne. Saachi started doing free legal work for people and they marched in some political protests.

In those days Lula dressed a bit like a punk and Saachi was mostly in silk saree. They must have looked very odd together, waving placards about mining and nuclear weapons. Lula says that watching the film Billy Elliot always makes her cry because it reminds her of being young.

When it was time for them to go home, Lula was sad about the end of university, so Saachi invited her to come back to India. They used the money they had saved from the market stall to pay for an extra ticket. As Lula says, the rest is history, but I’m sure there’s a lot she hasn’t told me.

After breakfast Priya and I hung around the garden for a bit wondering what to do. She was all for going back to the Theyyam on a hunt for Jonny Gold, but Saachi asked if we could help the protest by taking photographs of the mangroves that lined the waterways and protected the land. Mangrove trees grew right into the water, perched up on their twisty roots as if they were on stilts.

Saachi explained that the mangrove trees sucked up salty sea-water through their drinking-straw roots, recycling it into fresh water that could be used in the village vegetable plots. Saachi wanted to record how many there were before the developers started chopping them down. She gave me her camera and we dragged a rowing boat down to the river.

Priyanka and I sat at either side of the boat, with an oar each. But right away she went into full princess mode and for a while we just splashed round in circles, laughing and getting wetter and wetter. When we did manage to go in a straightish line, Priya’s oars got tangled up in weeds and lily pads and I was afraid we would capsize. In the end, I suggested she should just read her magazine and leave the rowing to me.

It was hard work, but after a while I got into the rhythm of twist, dunk and pull on the oars and the boat slid gently through the water, leaving only shallow ripples behind. Further up from the riverbank, big brightly painted houses, like Priyanka’s, sat partially hidden behind high walls.

Some of them were empty and they looked a bit bedraggled. I thought about taking photos of them for Lula, who liked that sort of thing, but I was on a mission for Saachi and I didn’t know how long the batteries would last. So I rowed on. Priyanka said the owners were away, working, like her dad, in Dubai.

‘I wish he wasn’t so far away,’ she said.

‘Yeah, I know what you mean.’

‘At least your dad lives in the same city.’ She snapped the pages of her magazine.

‘Does your dad come home often?’

‘Not so often lately, but he sends me really nice presents.’

I slid the oars into the water again. ‘What does he think about the hotel?’

‘He says it is a good thing because it will bring money and jobs. He thinks Amma gets too sentimental about the village.’

Then she said she kind of agreed with her dad about the development. She thought it would be nice to have some good shops and maybe a few rich tourists around. She told me that her dad got cross with Saachi for getting involved in stuff that he said wasn’t her problem.

‘But it’s good that she cares about people, isn’t it?’ I said.

She didn’t reply and I wondered how you knew for sure when something wasn’t your problem. The way Saachi talked abo

ut the environment seemed really personal, like she had decided one day to make it her problem no matter what anyone else thought. She was a bit like Dad – he made stuff his problem too. He got up a height about all kinds of things – mostly war, discrimination and people who didn’t pick up their dog’s poo.

I thought about them both, taking on the bad guys, like they were on a special mission to protect the world. Maybe one day I would be on a mission of my own. But what could I do? Perhaps recording the mangroves for Saachi was a good enough start. Tucking the oars into the side of the boat, I started taking the pictures she said she needed.

Priyanka dropped her magazine. It lay flapping in the bottom of the boat. Skinny models glowered from the glossy pages.

‘They don’t look like that in real life,’ I said to her.

‘What do you mean?’

‘They mess around with the pictures to make the clothes look better. Dad says they should be ashamed of themselves... I was so jealous when I first met you, Priya.’

‘Why?’

‘I thought I’d be something special here, just because I was from London, and then it turned out you were waaay cooler than me.’

‘Actually, I was also worried you’d be super-cool, just because you were from London. Imagine my disappointment!’ she laughed.

‘Oh very ha ha!’ I splashed her with river water.

‘I really wanted us to be best friends, Cass.’

She smiled at me and I realised my hands had stopped shaking. I picked up the camera and scanned the riverbank.

‘Do you want to be a lawyer like your mum?’ I asked Priyanka.

‘Actually, I would really like to be involved in the fashion industry.’

‘Lula reckons London is the world fashion capital. She’s been shoving brochures for design courses at me for ages,’ I complained.

‘I’d love to go to London, but I don’t think my father would approve.’

‘But Granny-ji is a big fan.’

‘Granny-ji’s never been! Her ideas about England all come from her old books. Once I heard her ask your amma how the London pea-soupers were these days.’

‘What’s a pea-souper?’

‘I have no idea. Your amma just laughed and said they’d been blown away with the bowler hats.’

I stared across the river, shading my eyes from the glare of the water with Saachi’s camera. While Priya talked about fashion, I snapped away until the low-battery light began to flash on the screen.

I picked up the oars and we splashed our way back to where the river joined the sea. I tied up the boat, and we went and sat on the beach. I checked the photos I’d taken. I hoped they were good enough. It looked like they were all in focus and I hoped Saachi would be pleased. I even managed to add the date and time to the album.

We swam for a bit, and then, after arranging to meet up later at the house, I left Priya on the beach with her magazine, and walked down the path which led to the netball court.

As I got closer, I hoped I would hear the shouts of a match going on, but there was no one around. A metal fence had been put up all around it and the gate was padlocked. The goal posts had already been sawn through ready for the bulldozers. They lay on the ground like felled trees, the ribbons on the hoops trailing on the dusty ground.

Seeing the empty court made me feel really sad for Nandita. I was glad I was doing something to stop the development now and I wondered when I’d see Dev again, so I could tell him.

Up on the hill, away from the beach, was the fencing which surrounded the new hotel development. A red truck was parked by the entrance gate. I wanted to get a few photos of the site for Saachi, so I turned off the path and started to follow the steep track upwards.

As I reached the top I heard voices coming from near the sign board. I couldn’t understand the words, but one of the voices sounded familiar.

I suddenly felt really uncomfortable, like I was eavesdropping on someone I knew and it was too late to let them know I was there. I didn’t want to be seen, so I ducked down behind the truck. The voices got louder and a man laughed. Now I was certain I knew his voice. Gravel crunched as the man walked away from me, and I stood up to get a better view.

Even from the back I recognised him.

It was Call-me-V.

He was holding a brochure with a picture of the new hotel on it and shaking hands with a man in a suit who seemed to be showing him around. Whatever Call-me-V had done, it had obviously made the man very happy. I ducked back down behind the truck.

What was Call-me-V doing here? Why was he being all buddy-buddy with the hotel developers? I knew he was a businessman like Priyanka’s dad so maybe he thought the hotel was a good idea too.

I raised the camera to my face and zoomed in on the brochure and Call-me-V’s head. His big cheating smile was in perfect focus. Seeing it super-sized, I felt furious. What a creepster, pretending all the time to be Saachi’s friend. If Saachi found out she would go beyond Kali.

Then, with a rush of excitement, I realised I was right about him all along. Now all I needed to do was tell Lula and she would see him for the double-crossing stranger that he was and probably call off the wedding.

I pressed the green button and heard the camera whirr and click. It wasn’t a loud noise but call-me-V looked across the bonnet of the truck and seemed to stare right at me. I felt my face flush and put the camera down.

There was no one at the house when I got back. I ran from room to room, looking for someone to tell my big news, but they were all empty and Saachi’s car had gone, too. Even Priya had gone off without me.

I took a shower and then went to the kitchen and made myself a drink and a snack. It was weird being here alone. The house was quiet and every sound I made echoed in the empty rooms. I fetched my iPod, but the batteries were dead.

My Peacock book was lurking under a chair on the terrace. I had nothing else to do so I cracked it open again and caught up with the misery fest that was Una’s life.

Her very wicked stepmother, Alix, was shopping in Paris and Una was off with her dad on an amazing sightseeing trip round India. But she wasn’t having a good time and kept being sick. Una missed the poet boy too, but she didn’t tell her dad about him.

I thought she should, just as I wished Lula had told me about Call-me-V. Secrets just got in the way and made stuff even harder. Then I remembered I hadn’t told her about Rachel either. Maybe, like me, Lula just never found the right time.

‘Oh, there you are. I’ve been looking for you for ages, Cass!’ said Lula, appearing on the terrace. She sat cross-legged on the ground. All the spiky energy she’d been carrying around was gone. She looked really tired and a bit sad.

For a while Lula and I just sat staring out into the garden. She had stretched out her legs and her feet lay grilling in the sun. Her toes were already going pink. I realised I could tell her about Call-me-V now. Dish the dirt about him and the developers. Then she’d realise that he was the wrong person for her and start paying me a bit more attention.

‘Mum, can I tell you something?’

‘Of course, Cass, but do you mind if I go first?’

Typical, even when I found the right time to say something, it was wrong. I shrugged my shoulders and she took a deep breath, blowing the air out through her lips as though she was about to jump off a very high diving-board.

‘The shop is in trouble, Cass, and I’m going to have to close it down.’

‘What?’

‘I’m so sorry, Cass. It’s been losing money for a while and Auntie Doré says the January sale has been a disaster. I’ve finally run out of time and money. I hate to do this, the shop means everything to me, and I know I’ve let you down, but I don’t have any other choice.’ She said it all in a rush as though she didn’t dare to stop.

I couldn’t believe what she was telling me. It had to be a mistake or some kind of horrible joke. I thought about our lovely shop. The way it smelled of incense and lemongrass. The rich colours of the

cushions and rugs I lay on to play with my dolls when I was little. People’s faces breaking into smiles when they walked through the door. It was our little palace and Lula was the queen bee. No wonder she’d been stressy.

‘I thought the shop was doing really well... why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I didn’t want to disappoint you, Cass. You like all your nice things.’

She was making it sound like it was partly my fault, that keeping the shop was done for me.

‘What about our celebrity clients?’

‘They’ve moved on to the next trend. I think Mongolia is the new kid on the block now.’

‘Can’t Auntie Doré help?’

‘She said she’d put money in, but only if I find a new range to sell.’

‘What about Dad?’

‘Your dad has his own life now. It’s my shop. It’s broken and I don’t know how to fix it, but I won’t ask your dad to throw his money away too.’ She stared out into the garden and started twisting her earrings.

My head was still spinning, and I didn’t really believe what Lula said could be true. But my body felt as if I’d been running downhill really fast. There was a panic feeling in my chest and my arms and legs were all shaky.

I took a couple of deep breaths. ‘But how could you let this happen?’

‘I’m sorry, Cass. I kept hoping things would change and they didn’t and then it was too late.’

I didn’t want to be angry with her, but I was. My whole life was going down the tubes and it was her fault. Mean, spiteful words jumped into my head and fizzed there. It would be so easy just to let them out, to blame her for everything.

Yet it wasn’t really her fault. I knew how hard she worked and how much the shop meant to her. She didn’t mean for it to turn out this way.

I looked at her hands twisting at her earrings and watched the expression on her face as she tried to pretend everything would be OK. I realised how much it must have cost to buy my plane ticket. She could have just left me with Dad, but she knew I was unhappy and lonely and so she brought me with her, even though it must have made her money troubles even worse. I felt a big wave of love surge up from my toes to the top of my head.

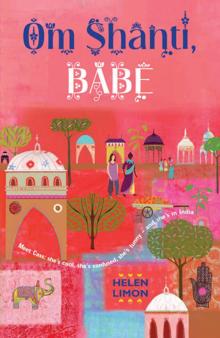

Om Shanti, Babe

Om Shanti, Babe